Character Assassination in a Major Key: Ozzy’s Reputational Victory

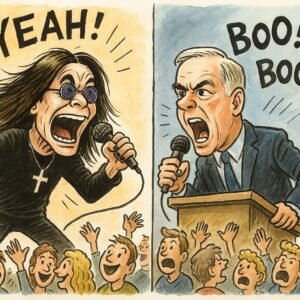

It took just one off-key scream—an awkward, guttural “YAAAAAH!”—for Howard Dean to be tossed off the national stage. One soundbite, looped endlessly, and his presidential hopes evaporated in 2004. Meanwhile, Ozzy Osbourne built a four-decade career on screams—bloody, guttural, gloriously indecent—and became a legend.

The lesson? Reputation is not earned or destroyed by actions alone, but by how those actions land within a cultural script. What’s political suicide in one sphere might be a career jackpot in another.

In politics, image is oxygen. A lapse in decorum, a scandalous affair, or even an impromptu scream can trigger a reputational avalanche. Just ask Gary Hart, once the Democratic Party’s rising star—until a yacht, a model, and a camera shutter brought him down. That was the 1980s. Since Reagan, however, more and more politicians seem coated in Teflon: gaffes, affairs, even indictments often fail to stick the way they once did. Yet character assassination still lurks at the margins, ready to strike when timing and optics align.

Entertainment, however, plays by different rules. In pop culture, eccentricity is currency. The weirder, the wilder, the better. Transgression is not a sin—it is branding. Yes, you can fall (ask Milli Vanilli in 1989 who were lip singing), but only when you break an unspoken rule, like faking authenticity. Ozzy didn’t fake it. He tore through the stage like a goblin on a bender and then—famously, infamously—bit the head off a bat mid-show in Des Moines. Was it a mistake? Maybe. But it made him unforgettable.

We don’t remember the exact songs. We remember the bat.

Growing up in a big European city, I didn’t listen to Ozzy much. But his name was everywhere—graffitied in tunnels, carved into school desks, scrawled like a curse. Or a prayer. Ozzy meant chaos. Ozzy meant cool. It was good to look bad—and no one looked worse, or better, than Ozzy Osbourne.

In the 1980s, he wasn’t just making noise—he was making enemies. Moralistic parents and pundits clutched their pearls during the Satanic Panic and painted Ozzy as rock’s Antichrist. Lawsuits followed, including one accusing him of encouraging teen suicide through his lyrics. The courts dismissed it. The public didn’t. Ozzy became a symbol of rebellion and unfiltered flamboyance.

He was getting older, but he didn’t vanish. He didn’t retreat. He evolved.

When The Osbournes premiered on MTV in 2002, the transformation was nothing short of surreal. The Prince of Darkness had become a doddering, foul-mouthed dad, muttering about remotes and stomping around in slippers. America fell in love. Professors—my own colleagues—asked me to record episodes on my VCR just to keep up. Ozzy was no longer the villain; he was the punchline. And he owned it. Sort of.

This arc isn’t Ozzy’s alone. Alice Cooper painted his face and faked his death on stage long before Ozzy, courting outrage with glee. He was rock’s first pantomime villain, scaring parents and thrilling teens. Then there’s Courtney Love—equal parts poet, punk, and tabloid magnet. Media painted her as a chaotic widow, overshadowing her immense talent with sexist caricatures of instability.

But Ozzy stands out. He didn’t apologize. He didn’t correct the narrative. He embraced it. He let the myth swell until it burst, and then he reinvented himself—without denying who he had been. He didn’t just survive character assassination. He turned it into an art form.

That is a lesson worth studying. Politics demands dignity. Pop culture demands flash. Rock culture demands mayhem. Each domain has its own thresholds—and its own forms of reputational capital.

There are limits, of course. Even in rock, betray the wrong unspoken rule—say, hurt a fan or fabricate your work—and your halo turns to ash. But reputational survival often boils down to one thing: control of the narrative.

Lee Sigelman, a political science professor I admired, once shared with me a rule for unknown candidates: don’t start with your platform. Nobody cares. Instead, do something—anything—that gets you noticed. Be outrageous. Then pivot to substance once you’ve got the mic. It worked for many politicians. It was Ozzy’s playbook.

From a CARP lens, Ozzy’s story shows how character attacks harness cultural fears—of chaos, youth, transgression—and how those attacks can sometimes backfire into myth-making. If timing and culture are right, even being labeled “dangerous” can read as authentic, even heroic.

Is Ozzy proof that bad behavior is good branding? Not exactly. He’s proof that reputations are rubber, not glass. They bend, warp, snap back, and sometimes, become stronger under pressure. That’s the ultimate CARP takeaway: reputations don’t live or die on scandal alone. They live and die by who controls the story—and whether it is louder, messier, or more magnetic than the smear written against you.

While some reputations die in a scream, others scream their way into legend.

Useful sources:

Blecha, Peter. (2004). Taboo Tunes: A History of Banned Bands & Censored Songs. Backbeat Books.

Weinstein, Deena. (2000). Heavy Metal: The Music and its Culture. Da Capo Press.

Osbourne, Ozzy & Ayres, Chris. (2009). I Am Ozzy. Grand Central Publishing.

McLeod, Kembrew. (2001). Owning Culture: Authorship, Ownership, and Intellectual Property Law. Peter Lang.

MTV. (2002–2005). The Osbournes [TV Series].